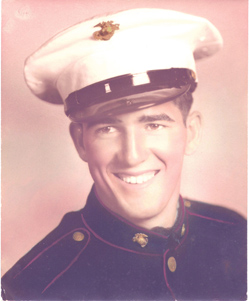

Dominic Spitale

Dominic Spitale grew up in a large poor immigrant family in western New York State. He joined the Marines as much to help his mother as to help win the war. Every month he sent home forty of his fifty dollars pay. On Okinawa he was shot through the temples and left for dead until someone saw him move on a field covered with corpses. Unidentified and in a coma for months, he got married while still recuperating and had to check in from hotel to hospital at ten each night on his honeymoon. He worked two jobs most of his life—at a factory and in a church—to support his family. Close combat left him with a horror of violence. “After the war,” he says, “I never wanted to hurt anything again, not even an ant. I got it in my head they’re here for a purpose.”

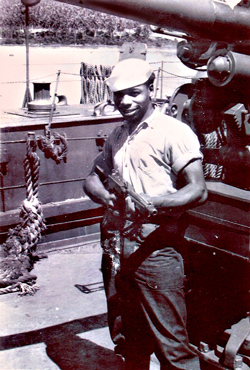

Robert H. Yancey

Jacob Sahl's Flight Crew

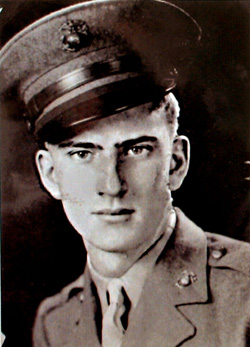

Bill Barber

Private Bill Barber grew up in Boston and, like most other 18-year-olds at the time, was seized with patriotic fervor after Pearl Harbor. Guys cried, he remembered, if they were turned down for service. A lonely raw replacement in a squad of hard-nosed regulars, trudging up a mountain on Luzon to clear out enemy hiding in caves, excitement faded as truckloads of dead GIs stacked like cordwood passed them coming down. Fear was a constant companion, he says, and you fought, not because of patriotism, but for the guy next to you. When he was discharged, he studied journalism on the GI Bill and became a sports writer.

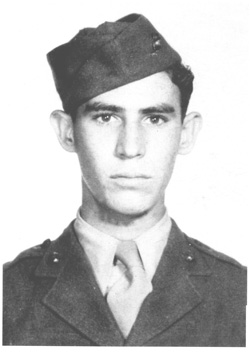

Donald Mates

Donald Mates, an Ohio Fireman’s son who joined the Marines because “he liked the uniform and thought war would be like the movies”, never got over the carnage he witnessed on Iwo Jima. A successful real estate developer, now retired, he recently went back to the hill where a grenade landed between his legs, met Japanese survivors and, only then, was able to let go of the hatred that had festered ever since

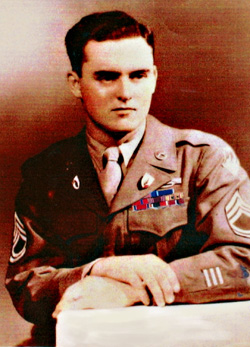

Anthony Daddato

Army Sergeant Anthony Daddato lost his best friend to friendly fire and contracted dengue fever and malaria on Saipan. Complications led to tuberculosis and he spent 3 embittered years in hospitals before a feisty nun’s advice changed his outlook. He went to school on the GI Bill, became an optician and ran his own business for 25 years. He still works part-time and lives in the first and only home his parents owned, on a modest row in Queens, New York, the house where he was wed, raised his children and became a widower after 46 years of marriage. Energetic and gruffly humorous, Tony’s eye for the ladies is undimmed: he has a new girlfriend.

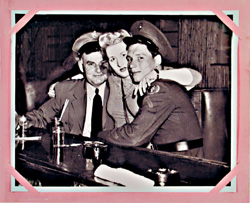

Howard Terry (on right)

Howard Terry’s stepfather didn’t want him around so his mother put him in the Tennessee Industrial School. He lied about his age and joined the Marines at 15. After five years in the Nashville institution—where barefoot, bareheaded boys worked in the bean fields and were beaten if they didn’t meet a quota—he says boot camp was a snap. The horror of combat was a different story. Traumatized by his accidental killing of an Okinawan boy, he returned home angry, belligerent and unable to hold down a job. Eventually, he married, had a family and learned a trade, burying his memories in the solitary, quietly ticking world of the watchmaker. He and his wife celebrated their 58th wedding anniversary in August, 2005.

PFC Giles McCory

Giles McCoy was three decks below when the USS Indianapolis was hit by torpedoes. In one of the worst naval disasters in history, the ship carrying 1200 sank in twelve minutes. He dug his way out and helped save dozens of men trapped under debris, then spent five days in a life jacket kicking off sharks. The former Marine sniper returned home racked with guilt over the people he had killed and determined to “do something with his life”. A deeply religious man who lost two of his brothers in the war, he became a family doctor, making house calls in rural Missouri for 37 years in a kind of lifelong act of atonement.

E. O. Bud Clark

Eugene “Bud” Clark, a pint-sized former Marine from a military family in Macon, Georgia, mowed down Banzai warriors, watched mass suicide on Saipan and was severely wounded on Iwo Jima. He says his war experiences made him “appreciate the value of life” and taught him “sticktoitiveness” and self-assertion. Like most of the veterans on this program, he has been married to the same woman for over 50 years. He rose through the ranks in a long career with Eastern Airlines before retiring to Florida. |